Since the launch of ChatGPT, I’ve become ever more fascinated by how we interact with AI. ChatGPT and other chatbots have gone through several updates and changes. From large changes like the ability to talk with them through our voice, to more nuanced details like changing how the text is displayed as it is being generated. This picqued my interest, and the interest of three other fellow students of the AI Master’s program at the University of Utrecht. So, together with Lisa Aaldijk, Gijs van Nieuwkoop, and Marc Overbeek we decided to investigate the effect of different response delays on human-AI interaction by creating a chatbot and then testing it on 40 people.

I expected to confirm what seemed intuitive: that making chatbots act more human-like would improve the user experience. What we found instead has made me rethink some fundamental assumptions about human-AI interaction.

The Theory Behind Human-AI Interaction

Before diving into our study, it’s important to understand the theoretical foundation we were working from. In the field of human-computer interaction, one of the most influential frameworks is the “Computers Are Social Actors” (CASA) paradigm, developed by Nass and Moon in 2000. This paradigm suggests something fascinating: humans naturally apply social rules and expectations from human interactions to their interactions with computers.

When I first encountered CASA, it made intuitive sense. We’ve all caught ourselves saying “thank you” to Siri or feeling frustrated when a chatbot “ignores” our question. According to CASA, these aren’t just quirks – they reflect a fundamental aspect of how humans process social interactions.

This paradigm has heavily influenced chatbot design. Designers have incorporated various “social cues” to make interactions feel more natural: giving chatbots names and personalities, adding typing indicators, and implementing conversational patterns that mirror human dialogue. Research by Feine et al. (2019) even created a comprehensive taxonomy of these social cues, showing just how extensively designers have tried to humanize these interactions.

Why Response Delays Matter

One particularly interesting aspect of this is how chatbots handle response timing. In human conversation, we expect certain natural delays and signals – like seeing someone type or pause to think. Before ChatGPT, researchers like Gnewuch et al. (2018) found that adding typing indicators increased perceived social presence, especially for users new to chatbots.

But the landscape has changed. With the emergence of large language models and their widespread adoption, users’ expectations and experiences with AI have evolved. This is what made our study particularly timely.

Our Experiment

We designed our study to test whether these established principles still hold true in today’s context. We compared three different approaches:

- A simple blank screen during the delay

- Three dots appearing one at a time

- Text appearing character by character (like human typing)

We built a restaurant-recommendation chatbot and had participants interact with it under all three conditions. Each response was delayed by two seconds, and we measured perceived usability after each interaction using Holmes et al.’s (2019) validated questionnaire.

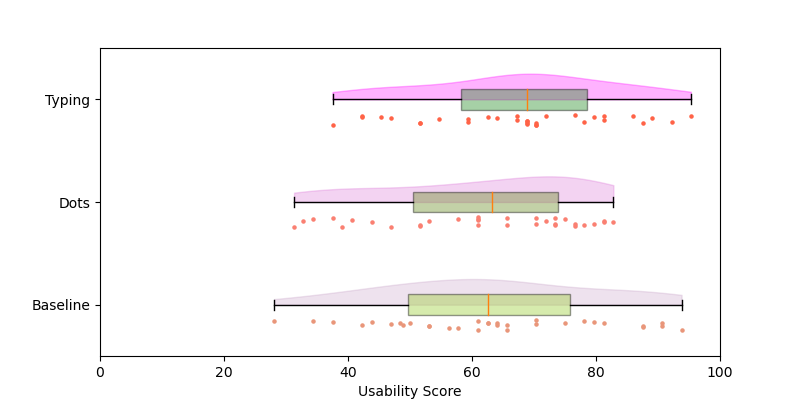

Results

The results weren’t what we expected. We found no significant difference in perceived usability between the three approaches. This challenges the common assumption that making chatbots more human-like automatically improves the user experience.

Limitations

Of course, as with any study, there are limitations to consider. Our interactions were relatively brief, and we used a short delay time. I’m particularly interested in exploring how these findings might change with more complex interactions or longer delays.

We also used convenience sampling, which likely limited our findings’ generalizability.

A Shifting Paradigm?

Even though our findings are not conclusive, they do make me wonder if we’re witnessing a shift in how CASA applies to modern AI interactions. Previous research suggested that social cues were crucial for user experience, but our results hint at a more nuanced reality. Perhaps as AI becomes more sophisticated and commonplace, users are developing new mental models for these interactions – ones that don’t necessarily require human-like behaviors to feel natural or useful.

This doesn’t invalidate CASA, but it suggests that its application might need to evolve as users become more AI-literate. The social rules we apply to AI interactions might be developing into their own unique set of expectations, distinct from both human-human interaction and traditional computer interaction.

What This Means for AI Design

I believe our findings, while not conclusive, lead to the following ideas, as food for thought:

- Users might be more accepting of AI interfaces that don’t try to mimic human behavior than previously thought.

- Users may actually prefer interfaces that embrace AI’s unique characteristics – like rapid processing, data-driven insights, and systematic problem-solving – rather than those trying to emulate human conversation patterns.

- Design efforts might therefore be better directed toward creating intuitive interfaces that complement AI’s strengths rather than masking its machine nature.

Moving Forward

This study has changed how I think about human-AI interaction design. Instead of asking “How can we make AI more human-like?” perhaps we should be asking “What kind of interaction best serves users’ needs?”

As AI becomes more integrated into our daily lives, understanding these nuances becomes increasingly important. While our study focused on one specific aspect of chatbot design, it raises broader questions about how we should approach human-AI interaction.

I believe we’re entering a new phase in how people interact with AI – one where users might be more comfortable with AI being AI, rather than trying to be human. As I continue my research in this field, I’m excited to explore what this means for the future of user experience design.

What do you think? Have you noticed changes in how you interact with AI systems? I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

References

Nass, C., & Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and mindlessness: Social responses

to computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56 (1), 81-103. Retrieved from

https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0022-4537.00153

doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00153

Feine, J., Gnewuch, U., Morana, S., & Maedche, A. (2019). A tax-

onomy of social cues for conversational agents. International Jour-

nal of Human-Computer Studies, 132 , 138-161. Retrieved from

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1071581918305238

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2019.07.009

Gnewuch, U., Morana, S., Adam, M., & Maedche, A. (2018, 12). “the chatbot

is typing . . . ” – the role of typing indicators in human-chatbot interaction.

Holmes, S., Moorhead, A., Bond, R., Zheng, H., Coates, V., & Mctear,

M. (2019). Usability testing of a healthcare chatbot: Can we use

conventional methods to assess conversational user interfaces? In

Proceedings of the 31st european conference on cognitive ergonomics

(p. 207–214). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machin-

ery. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1145/3335082.3335094 doi:

10.1145/3335082.3335094

Paper

Read the full paper here:

Leave a Reply